“aay” Belong in Montana

That’s right, “aay” (bull trout to the Salish and Kootenai tribes) really do belong in Montana. In fact, you could say they’re the first native Montanans, well, one of them anyway. Long before the first European explorers set foot in the Flathead; in fact, long before the first Salish and Kootenai peoples trod these grounds, the bull trout swam in our rivers and streams. There weren’t three forks of the Flathead as we know them today. In fact, we can’t be sure what it looked like back then, but we know the bull trout were here. When those first native American tribes settled in what is now the Flathead Valley the bull trout were there to greet them and became a vital part of their lives and their heritage.

And that was the thrust of last night’s program, The History and Cultural Significance of Bull Trout to the Salish and Kootenai Tribes. I know, that’s a mouthful, but Thompson Smith, Historian and Geographer, for the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes (CSKT), converted it to a fascinating glimpse into the history of the Flathead Valley and man’s relationship with a fish.

It is sobering to think that a hundred and sixty years ago bull trout were so plentiful that they could be found all the way to Butte, where they were so abundant they could be taken with bows and arrows. Northwestern Montana was full of bull trout, large bull trout, fish over three feet long and weighing up to 20 pounds! Fish called “salmon trout” by the first white explorers to venture into the area. They were an important source of protein for the tribes and unlike many other forms of game, were available year-round. Many place names included “aay” in their titles, long ago replaced with more familiar sounding names like Missoula, or Clark Fork. Bull trout were the lifeblood of the tribes; until they weren’t.

What changed? Everything. Industrialization, mining, smelters, logging, dams, the railroad, and on and on. You know the story, it’s been told many times in many places, and the bull trout got caught up in it. Eradicated from some waters entirely, remaining populations found themselves reduced in size and squeezed into smaller and smaller areas. What remains is just a remnant of what once was.

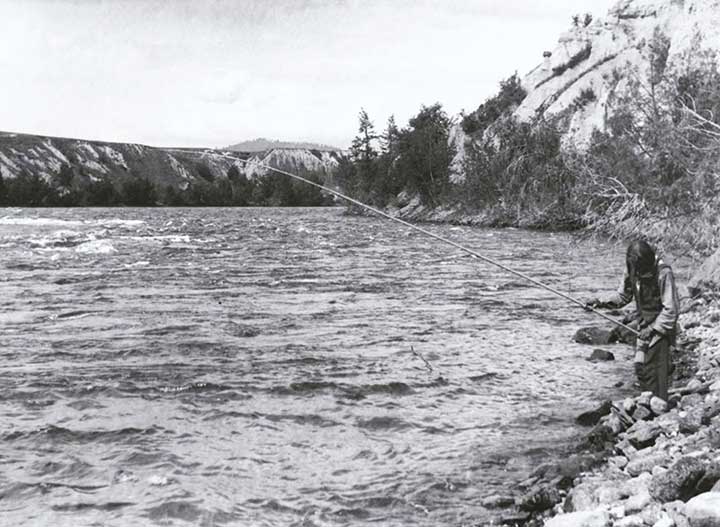

Up until the mid-1980s the bull trout population in the Flathead remained pretty stable. Talk with any local “old timer” and they can tell you stories of catching big bull trout in the Flathead system. An Internet search will turn up plenty black and white photos of stringers full of huge bulls. All was rosy until Mysis shrimp arrived in Flathead Lake, the kokanee population collapsed, lake trout became the apex predator, and juvenile bull trout became their favored food; but that’s a story for another blog.

If the 1980s seems like ancient history to you then you don’t have to look any further back than 2024. In just the last twelve months we’ve seen a big change.

Regardless of how you feel about dams. The completion of Hungry Horse Dam in 1953 resulted in an unintentional and unexpected benefit; it trapped an entire population of bull trout upstream in the South Fork of the Flathead River. Unable to reach their adfluvial home in Flathead Lake, they adopted Hungry Horse Reservoir as their new winter residence. The dam also blocked the upstream migration of the bull trout’s number one bane, lake trout. Without lakers to feast on their young, the South Fork bulls flourished. That resulted in a population strong enough to support the only legal bull trout fishery in the Flathead basin. It was, albeit, a shorter season, the third Saturday in May through the end of July. And it was strictly catch-and-release, but it was a season none the less and it provided anglers with an opportunity to catch bull trout and get, at least a sense, of how things were in the past. Those South Fork bulls did well, with some growing close to four feet long.

All was well and good until last year. A warming climate, lower snowpacks, reduced stream flows, higher water temperatures, and an excess of beaver dams in the spawning streams resulted in a dramatically reduced redd count. Those low redd count numbers crossed a threshold which triggered a reduction in the season. This year you will only be able to fish for bulls in the month of July, thirty-one days, that’s it. The next threshold is no season at all. Then what? A remnant population barely holding on, or full extinction?

It doesn’t have to be this way. As a kid I can remember reading about the Whooping Crane in Junior Scholastic magazine. At the time there were only about two dozen left in the world. Residents of the Central Flyway, they were very much on the brink of extinction. Thanks to the efforts of scientists, wildlife experts, and volunteers they were brought back from the edge. Today they number 600-800. That’s not a lot, but it’s way more than zero. The point is, we can make a difference and we can save a threatened species.

Bull trout are at risk and those risks are increasing. Maybe we can’t fix everything, but we owe it to ourselves and the bull trout to fix the things we can. We’ll never see bull trout numbers like the Salish and Kootenai tribes once experienced, but we can prevent your grandkids from sitting on your lap and asking “why did the bull trout go extinct”?

Afterall, “aay” belong in Montana!

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

We’re indebted to Thompson Smith for a great presentation, which regrettably was very poorly attended by our membership. Unfortunate, since saving our native species is a bit more important than knowing what fly to use to catch them.

Last night also marked the end of our general membership meetings for the 2024-2025 season. We’ll meet again next month for our annual banquet, Saturday, May 17th, at Grouse Mountain Lodge in Whitefish. This is always a hoot with lots of auctions, raffles, food, friends, and camaraderie. Bring your friends and family and plan on having a good time. For more about the banquet, and to purchase tickets click here: https://flatheadtu.org/annual-banquet-information/

See you there!