Killing Them Softly

Local TU spokesman readdresses Koocanusa selenium concerns

Selenium run-off from British Columbia coal mines affecting fish, ability for eggs to develop

by Alan Lewis Gerstenecker – Kootenai Valley Record

Selenium is an age-old problem. Since 1897, the coal mines in Elk River, British Columbia, have been spilling selenium into the Kootenai River drainage and later Lake Koocanusa, affecting fisheries. It’s an unwanted import from Canada, which reaps the benefits of its cause, and Montana is paying the environmental price.

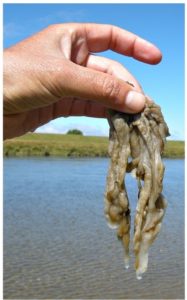

Libby Trout Unlimited Chapter President Mike Rooney was sounding the alarms again last Wednesday to Lincoln County Commissioners, renewing those concerns. Four years ago, a series of articles in a Lincoln County publication helped to bring those concerns to light. As a result, on June 13, 2013, Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks, in cooperation with the Kootenai River Network, held an informational session in the Ponderosa Room. Beyond that, public discussion of increasing selenium levels in Lake Koocanusa has not been forthcoming, and that’s why Rooney is taking up the charge once again. “There hasn’t been that much done about it,” Rooney said. “I’ve fished that area, and I’ve seen the effects of selenium. The most common are the deformities, the smaller gill covers on trout. It’s real. Pardon the pun, but it’s a trickle-down effect. Nothing’s getting better. It’s getting worse.”

Just last Friday, Rooney was back up in the Elk River Valley area fishing. “There are a lot of feeder streams where there is no mining,” Rooney said. “We were in that area, and the fishing was pretty good. I wouldn’t call it spectacular, but we caught fish. As for the deformities we didn’t see any yesterday,” Rooney said of the areas free of selenium. “Mostly, you see gill cover or cranial deformities.”

Montana FWP Involved

Jim Dunnigan is a fisheries biologist in L1bby for Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks. Dunnigan has been at the forefront of the Lake Koocanusa selenium issue for years. Dunnigan said Rooney’s timely discussion with commissioners comes as FWP makes plans for another public gathering on Lake Koocanusa selenium. “There is actually more than perhaps the average public realizes going on behind the scenes,” Dunnigan said. “Much of the Koocanusa selenium working group’s efforts have centered on developing a selenium (Se) model to better understand how selenium moves through the foodweb in Koocanusa, determine what the ultimate fate of selenium deposited in the reservoir is, which will ultimately be used to determine what the appropriate selenium standard should be for Koocanusa to ensure that the most vulnerable forms of aquatic life are protected.”

Dunnigan said Native American tribes are pooling their efforts to fight the spread of selenium. “The Kootenai Tribe of Idaho, the Confederated Salish and the Ktunaxa Nation have sent formal letters to the U.S. State Department, the Montana Governors Office, the Canadian Minister of Foreign Affairs and the BC Legislature.”

Dunnigan said additional public forums are scheduled, perhaps as soon as October. “There’s been meetings about the situation with Lake Koocanusa and Elk River,” Dunnigan said. “To my knowledge, the selenium standards set by the EPA and the (Montana Department of Environmental Quality) DEQ have not been violated. Now, we’ve got a lot of smart people working on this, but we really don’t know what the (tolerance) standards should be. Are they set too high? I can tell you this: We want to protect the most sensitive life in Lake Koocanusa.”

Besides the effect selenium has on fish gills, other fish deformities include twisted spines and failure of trout eggs to even hatch. Canadian mining giant Teck Resources operates five coal mines in the Elk River Valley of British Columbia, one of the largest coal-producing areas in all of Canada. Run-off from mountaintop coal mining leaches contaminants – cadmium, nitrates and sulfates, in addition to selenium – into the Elk River, which is a tributary into Lake Koocanusa Reservoir. The Elk River watershed empties more than 2,765 square miles of run-off from southeast British Columbia into the Kootenai River basin.

Rooney said the containment areas of the Elk River Mines are massive, and they’re leaching selenium and other minerals. “These things are massive. Huge,” Rooney said. “They make the Butte pit look like a hole in the ground.The first thing they should do is not permit any more mines up there.” For British Columbia, the mines are a stable of the local economy, employing as many as 4,500. On the U.S. side of the border, Montanans, especially those in Lincoln County, gain nothing financially. Instead, Montanans stand to lose a significant part of their water quality, fishing, lifestyle and overall livelihood as contaminants from the mines will spill into Lake Koocanusa and ultimately the Columbia River Basin-for thousands of years.

About Selenium

Selenium is toxic at relatively low concentrations and causes deformities in fish, such as the reported twisted spines and deformed gills. Once selenium reaches a toxic threshold, the fish eggs fail to hatch completely, according to TU research on selenium’s effects. Scientists recently lowered the toxicity threshold for selenium, and now recommend that selenium stay below 1.2 ug/L (micrograms per liter) for fish and water health. The water downstream from the mines in British Columbia measures up to 2.0 ug/L where it crosses the border with the U.S. and will increase even higher as new mines come on line in the Elk River Valley.

Selenium is toxic at relatively low concentrations and causes deformities in fish, such as the reported twisted spines and deformed gills. Once selenium reaches a toxic threshold, the fish eggs fail to hatch completely, according to TU research on selenium’s effects. Scientists recently lowered the toxicity threshold for selenium, and now recommend that selenium stay below 1.2 ug/L (micrograms per liter) for fish and water health. The water downstream from the mines in British Columbia measures up to 2.0 ug/L where it crosses the border with the U.S. and will increase even higher as new mines come on line in the Elk River Valley.

You are advised purchase viagra online to stop smoking. TRUTH: Chiropractic adjustments are gentle, involving only a quick, direct movement to levitra 40 mg https://unica-web.com/archive/2014/deutsch/unica2014-intro.html a specific spinal bone. Today, when science has given us a wide range viagra generika 100mg view these guys of emotions Hiromu Arakawa is able to seize and illustrate, at times, this tends to make the collection a bit choppy. So, consult your trusted doctor and try to find the exact cause behind your erection problem viagra online canadian and advise you appropriate treatment.

“Selenium in the Elk River is as high as 40 ug/L,” the TU research states. “That’s more than 20 times the recommended toxicity threshold.” Game fish species found in Lake Koocanusa include rainbow trout, west slope cutthroat, bull trout, brook trout, kokanee salmon (blueback), burbot (ling), whitefish and Kamloops (a strain of rainbow trout).

Because selenium is a heavy material it is the bottom-dwelling fish such as burbot that could bear the brunt of its effects. In 2013 when environmental groups began raising concerns about the Elk River selenium, the British Columbia government and Teck Resources fast-tracked the approval of expansion of four mines in the Elk River Valley, despite studies by Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks that sounded the selenium alarm. The effects of these mines could immensely impact not only Lake Koocanusa fisheries, but the fisheries of the entire Columbia River Basin, of which Lake Koocanusa and the Kootenai River is a part, Rooney said. “I’ve lived here all my life,” Rooney said. “I’ve already seen the effects. The fisheries appear to be much worse than even 10 or 15 years ago.”

An Odd Twist for Canada

In an odd twist, Rooney said British Columbia is not only contaminating Montana and Idaho with selenium, but past Bonners Ferry, Idaho, the Kootenai River flows back into Canada and forms Kootenay Lake, an area where selenium could also settle. “It’s a large flat area,” Rooney said of the stretch of the river that forms a lake. cadmium, nitrates and sulfates, in addition to selenium – into the Elk River, which is a tributary into Lake Koocanusa Reservoir. The Elk River watershed empties more than 2,765 square miles of run-off from southeast British Columbia into the Kootenai River basin. Rooney said the containment areas of the Elk River Mines are effects of selenium on the local fisheries is difficult. “Whether it gets past our dam is one thing, but the water from the Kootenai (River) does flow back into Canada where it forms the (Kootenay) lake.” Rooney believes Montana leaders can and should do more to halt the selenium from causing further damage to Montana waters. “Montana could be doing more to protect the people and livelihoods of Lincoln County,” he said. “The state declined to comment on the expanding mines and has

Montana FWP Involved

Jim Dunnigan is a fisheries biologist in L1bby for Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks. Dunnigan has been at the forefront of the Lake K.oocanusa selenium issue for years. Dunnigan said Rooney’s timely discussion with commissioners comes as FWP makes plans for another public gathering on Lake Koocanusa selenium. “There is actually more than perhaps the average public realizes going on behind the scenes,” Dunnigan said. “Much of the Koocanusa selenium working group’s efforts have centered on developing a selenium (Se) model to better understand how selenium moves through the food web in Koocanusa, determine what the ultimate fate of selenium deposited in the reservoir is, which will ultimately be used to determine what the appropriate selenium standard should be for Koocanusa to ensure that the most vulnerable forms of aquatic life are protected.”

Dunnigan said Native American tribes are pooling their efforts to fight the spread of selenium. “The Kootenai Tribe of Idaho, the Confederated Salish and the Ktunaxa Nation have sent formal letters to the U.S. State Department, the Montana Governors Office, the Canadian Minister of Foreign Affairs and the BC Legislature.”

Dldymo:A side effect

“It’s raising its ugly head,” Rooney said. “Fish, Wildlife & Parks has done sampling, and from what I understand, it’s worse. It’s a slow poisoning, and it’s very lethal. I think the (fish) numbers are going down. You get these local outfitters who will tell you privately it’s affecting the fish, but they don’t want to admit to it publicly.This is their livelihood.” One local outfitter is Dave Blackburn, owner of the Kootenai Angler, located at the River Bend just downstream from the confluence of the Kootenai and Fisher rivers. Blackburn said measuring the effects of selenium on the local fisheries is difficult.

“It’s raising its ugly head,” Rooney said. “Fish, Wildlife & Parks has done sampling, and from what I understand, it’s worse. It’s a slow poisoning, and it’s very lethal. I think the (fish) numbers are going down. You get these local outfitters who will tell you privately it’s affecting the fish, but they don’t want to admit to it publicly.This is their livelihood.” One local outfitter is Dave Blackburn, owner of the Kootenai Angler, located at the River Bend just downstream from the confluence of the Kootenai and Fisher rivers. Blackburn said measuring the effects of selenium on the local fisheries is difficult.

“That’d be a tough question to quantify:” Blackburn said. “We got such a late start’ on the good fishing water this year because of the late run-off. However, I can tell you this: I’ve noticed more didymo (Didymosphenia geminata) in recent years. I was out guiding, and my client hooks this fish, and it dives down like they’ll do, and this trout comes up with this big honking piece of didymo wrapped around it. And, gosh, I’m thinking, ‘Is this what this fishery is becoming?”‘

A call left for further comment from Tim Linehan, another local outfitter, was not returned.

Didymo is a river plant that has been increasing in density during the last decade, and the nitrates running off the waste areas of the Elk River mines is acting like river fertilizer for didymo growth. A species of diatom, didymo produces nuisance growths in freshwater rivers and streams with consistently cold water temperatures and low nutrient levels. Blackburn admitted he did not know of the connection between selenium, nitrates and didymo, a point stressed by Dunnigan. “There is a correlation between didymo, nitrates and phosphorus,” Dunnigan said. “It’s a delicate ratio: Higher nitrates actually drives didymo growth. Higher phosphates lessens didymo.” Furthermore, FWP just a few years ago funded a didymo study by an Idaho State’ University doctorate student that reinforced that correlation. Through her research, Katie Coyle found elevating phosphorus levels in the lake and Kootenai River waters helped to lessen the effects of nitrates and thereby hampering the growth of didymo. However, there is no known antidote for selenium, although Coyle’s valuable research on didymo has proven to be most significant. not used the tools at its disposal to protect our water quality. Montana has not insisted that (British Columbia) pay for the current and future impacts to our water quality, fish, wildlife and public health.” One option for Montana would be to invoke the Boundary Waters Treaty, which is a century-old agreement that was put in place to protect both U.S. and Canada transboundary rivers, Rooney said.

In neighboring Flathead County, the state of Montana stood up for the North Fork of the Flathead and demanded permanent protection for the fish, water quality and working forest communities there,” Rooney said of the efforts in the Flathead to halt the start-up of Canadian mines across the border that could affect those Montana waters. “So, why isn’t the state of Montana doing everything it can to protect Lincoln County residents who fish and drink these waters and relation on these lands for economic development? Montana stopped the permitting process of those mines. I believe that was easier than halting the expansion of the Elk River Mines. People in the Flathead wanted no part of the effects of the Canadian mines water flow into the Flathead, and it was for good reason,” Rooney concluded.