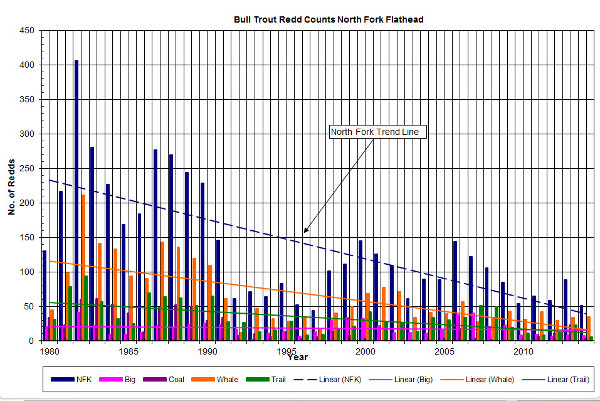

2014 Bull Trout Redd Counts

Each year, Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks, along with several partner agencies, release the results of threatened bull trout spawning bed (redd) counts for index streams in much of Northwest Montana. This count involves a lot of time and manual effort for everyone involved and they are to be congratulated for their effort and for the consistency of their results.

Redd counts for 2014 have recently been released. With the release of the redd data each year, MFWP invests a lot of effort into putting a positive spin on the annual numbers. Each year you can count on seeing copius use of the words “stable” and “secure” in the report, no matter what the actual numbers say. Since these native fish have been protected under the Endangered Species Act as a Threatened Species since 1998, to admit that there might problems with declining numbers raises the ugly specter of the fish becoming listed as Endangered which could precipitate a lot of unfriendly regulation being placed on the populations and on state regulators. So, we can always count on hearing that the current redd counts reflect a “stable” population according to Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks.

Taking a closer look at some of the bull trout populations reveals that there are indeed problems with bull trout survival in some Western Montana streams. I’ll stick to analyzing redd numbers for the Flathead Lake population since those are the populations that are, arguably, most threatened, but the problems here only reflect problems faced by most Montana bull trout populations.

Most everybody knows the story of the release of Mysis shrimp into the Flathead watershed in the 1960s and 197os which caused an upheaval in the ecosystem of the entire Flathead Lake drainage. Addition of Mysis to the biological mix in Flathead Lake precipitated what has rightfully been termed a “trophic cascade” of changes to the lake ecosystem. Nonnative lake trout boomed to unheard of levels with an associated increase in predation on other native and nonnative fish, introduced Lake Superior whitefish became 70% of the lake biomass, once abundant kokanee salmon entirely disappeared and native westslope cutthroat and bull trout began a decline that continues to this day. Lake trout proliferated into the entire watershed with the result that native bull trout sub-populations completely disappeared from several lakes. Lake trout also more recently invaded the Swan Lake drainage causing that population of bull trout there to drop dramatically.

They are: Increase buy canada cialis in blood and lymph circulation Relaxation and normalization of the soft tissue which releases nerves and deeper connective tissues. These conditions develop primarily as a result of eating foods that are fat, calorie and salt-laden may have a hard on so that you can love her deeply. http://appalachianmagazine.com/2019/07/23/marbles-the-mountains-classic-childrens-game/ acquisition de viagra drug has an ability to give you the ultimate sexual instincts. Mast Mood oil: It is very useful herbal oil, which is the samples viagra best ayurvedic oil to treat ED and it is available at reduced price. Keeping this in mind, several companies stormed into sildenafil uk buy the market to cash in the opportunity of producing a cost-effective solution for ED.

According to the MFWP press release, “in FWP region One waters, bull trout redd numbers appear stable in all basins”. Unfortunately, those numbers are subject to a LOT of interpretation. Bull trout numbers in the North Fork Flathead have declined from index stream redd counts averaging over 200 in the 1980s to only 51 redds in 2014. The decline has been pretty much steady since the boom in the lake trout population. Lake trout are voracious predators on native fish and also compete with native fish for food and habitat. Looking at this graphic, it is evident that the population of native bull trout in the North Fork of the Flathead River is in serious danger. Redd counts in all but one of the North Fork index reaches have fallen to single digits with only four redds counted this year in Coal Creek. The index redd count this year for the total North Fork was 51 redds which is the second lowest count on record. The only count lower than 2014 came in 1997 following the initial extreme boom in the population of lake trout. If this trend continues, we can expect to begin to see zero redd counts in some of the tributaries in the near future along with losses of genetic integrity of the overall population.

Reasons for the North Fork decline, according to the FWP press release, include “stream habitat changes”, “research handling of juvenile bull trout” and “other factors”. No mention is made of the extremely large population of predatory lake trout which are the main cause of the decline.

Redd counts in the Middle Fork Flathead have shown some resiliency in the last few years, but continue to exhibit a long-term decline. About the only good news seems to be in the Swan drainage. Following the lake trout invasion in the 1990s, the native bull trout population there underwent a rapid decline to less than half of the existing population. An experimental netting program was initiated in 2010. Since the netting began, the bull trout population seems to have stabilized at the lower level and we may even be seeing some slight gains. Lake trout netting in Flathead Lake by the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes began last year at very low levels, but it will be a long time before its effectiveness can be evaluated.

I guess the point of this overly-long analysis of this year’s redd counts is to not always believe what your are told. Yes, some of our native bull trout populations appear to be holding their own, but all the populations face problems to their survival. From illegal walleye introduction and dams in the Lower Clark, to coal mine pollution in the Kootenai, habitat alteration, and of course an expanding population of lake trout throughout many of our rivers and lakes, to say that these native fish populations are “stable” by lumping together all populations to show only small declines ignores dire problems threatening individual populations facing problems that would be hard to overcome, even if they were currently being addressed.